At a meeting in Tower Hamlets Town Hall, Mayor Lutfur Rahman is being roundly bollocked by a local petitioner over the council’s plans for Victoria Park. “Once again,” she proclaims, “the mayor has decided that he knows better than the Tower Hamlets people, that he can ignore the Tower Hamlets people and that he can cut out community groups as he sells off access to Victoria Park.”

Her disdain for the mayor and his newly founded Aspire party is not uncommon around here. One Aspire councillor attempts diplomacy, responding that, with the cost-of-living crisis, Tower Hamlets must administer its assets wisely. “I agree,” she replies, “and what’s more, I think it should start with the mayor’s office.” Applause erupts from Labour’s side of the chamber, acknowledging last year’s row over the mayor’s decision to spend around £450,000 of public money on an office upgrade, £50,000 of which went on a new meeting table and luxury chairs.

Rahman looks benevolently off into the middle distance. He’s not bothered. Why should he be? Following his landslide victory two years ago, he is more powerful than ever, having soundly beaten his Labour opponents in the race for mayor and for control of the council. On his side of the room, Aspire’s intake deliberate merrily. It’s easy to spot who’s who; whereas Labour has a mixed pool of representatives, Aspire’s councillors are exclusively British Bangladeshi men.

Rahman’s party is a strange one. Many of its councillors are political first-timers. The party has no website, no press enquiries inbox and its constitution is about as easy to access as Area 51. A freedom of information request revealed its mission “to promote independent democratic socialist values”, but that’s about the extent of what you can learn. Aspire’s base is local Bengalis, who make up about a third of the borough’s population. Rahman himself hails from Sylhet in eastern Bangladesh, as do 95 per cent of British Bangladeshis, one in six of whom live in Tower Hamlets, the youngest and most densely populated borough in England. But Rahman’s ambitions may extend beyond local politics. It has been reported that Aspire is considering fielding candidates in 30 parliamentary constituencies in the upcoming election.

Rahman has also expanded his appeal to young, left-wing voters, tacitly positioning himself as an inheritor of the Corbyn project. In 2022 Rahman hired Corbyn’s former political secretary, Amy Jackson, to be his chief of staff. He’s also brought in Karie Murphy, the executive director of Corbyn’s office. Kieran Andrieu—previously from Labour MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy’s team—now runs strategy alongside Nihal El Aasar, a Marxist researcher and resident DJ for the hipster radio station NTS. This is a symbiotic relationship: whereas Rahman’s focus seems to be the cultivation of power, one assumes Corbyn’s adrift ex-staffers see his mayoralty as a vehicle for concise progressive ends.

In this vein, spending on youth services has been ratcheted up, the council has become the first in England to provide free school meals to every child in both primary and secondary education, the Education Maintenance Allowance—a weekly grant awarded directly to high-schoolers, scrapped in England by the coalition government in 2010—has been reinstated and council-owned housing stock and leisure facilities have been brought back under public control. Rahman’s policy programme extends to Britain’s financial hub. In January, his administration announced its intention to take control of empty units in Canary Wharf, potentially pitting itself against supranational landowners.

And then, of course, there’s Gaza. Following Labour’s botched response to the Gaza war and an LBC interview in which Keir Starmer appeared to support cutting off water and fuel from the region (a war crime, according to international humanitarian law), British Muslims have been leaving the Labour party—a phenomenon one senior Labour source reportedly referred to as the party “shaking off the fleas”. Support among Muslims has fallen 43 per cent since 2019.

With a general election set for later this year and local elections coming up in May, Starmer’s office has been anxiously polling British Muslims, worried that the party’s Gaza stance has risked a core set of loyal voters. These anxieties were borne out in Rochdale in February with the election of George Galloway, who swept a parliamentary seat with almost 40 per cent of the vote, having attracted endorsements from both the town’s Muslim community and the infamous former far-right leader, Nick Griffin.

The Conservatives, meanwhile, are dramatically failing to alleviate concerns that their party has a serious Islamophobia problem. In February alone, one poll found that 58 per cent of Tory party members saw Islam as a threat to the “British way of life”; the former deputy chair, Lee Anderson, lost the whip for claiming Sadiq Khan was “being controlled by Islamists”; and former minister Paul Scully claimed parts of Tower Hamlets were “no-go areas”. In mid-March, Michael Gove suggested influential Muslim organisations Mend, Cage and the Muslim Association of Britain (MAB) could be deemed “extremist” under his new definition of the word.”

This is ripe territory for Aspire. Take a walk down Brick Lane and you might see a van fitted with LED panels, blaring music and imploring passersby to leave the party that betrayed the children of Gaza. In November, hundreds of protestors surrounded the office of Rushanara Ali, Labour MP for Bethnal Green and Bow, chanting “vote her out” after she failed to support a ceasefire. Likewise, almost every other lamppost in Whitechapel, Shadwell and East Bow (where Rahman grew up), had been adorned with a Palestinian flag until March, when Rahman, under pressure from the media and a threat of legal action, ordered their removal from council infrastructure.

“We want to see a ceasefire immediately. Your cries, your sympathies I fully understand,” The mayor said in November, addressing 400 students at a school walk-out in east London before asking them to get back to class. In January, The Muslim Vote (TMV), a grassroots group endorsed by the Muslim Association of Britain, said it had “thousands of volunteers, ready to support independent political campaigns in constituencies with a significant Muslim electorate.” TMV would likely throw its weight behind Aspire were it to run parliamentary candidates, especially in a borough with the highest Muslim population in the country.

Rahman is at the high-water mark of his career, riding a political wave that carries down Stepney, Bethnal Green, the Georgian properties of Spitalfields, the deprived estates of Poplar and breaks onto the glass towers of the Isle of Dogs. Perhaps it will even carry him up the Thames to Westminster. But things weren’t always this way. Go back seven years and you’d see a very different Lutfur Rahman. A man beaten by his own ambition, who had gained and lost almost everything.

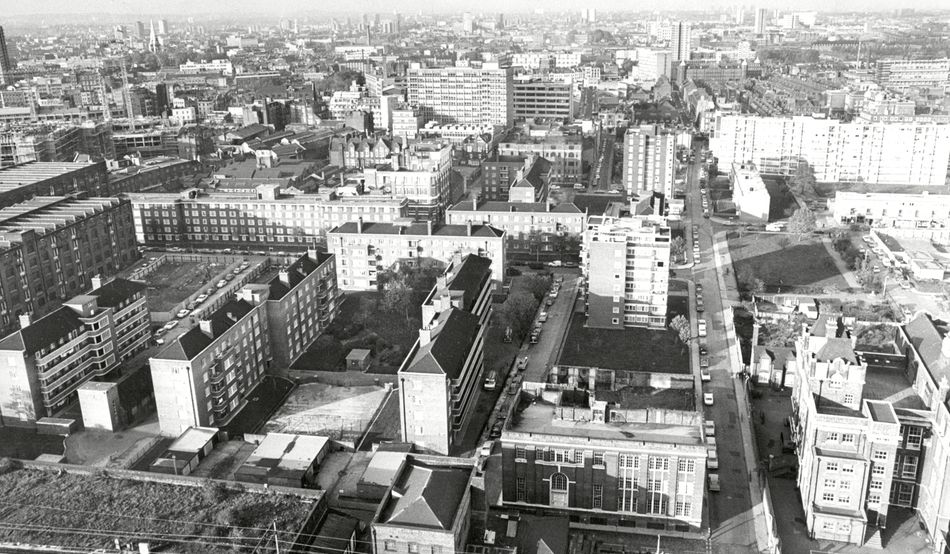

To understand Lutfur Rahman, you first have to understand Tower Hamlets. When the historian John Strype listed the area in his A Survey of London (1720), he might as well have been referring to Tolkien’s Mordor. He divided the capital into four component sections: the City of London, Westminster, Southwark, and “that part beyond the tower”. As Strype asserted, the East End was not London, but rather its dark, unruly byproduct. With the encroachment of industry, noxious tanning plants sprang up there because the prevailing wind stopped the foul smell reaching the rest of the city.

With time, the area’s cheap housing and proximity to the docks attracted successive waves of immigration. French Huguenots set up silk looms; Irish Catholics came to process the spoils of Empire in the docks; Jews arrived, fleeing pogroms in eastern Europe; and, in the early 20th century, the first Bengalis: lascars from the British Merchant Navy. At first only a negligible number arrived—about 150 until 1940—then, in the early postwar period, a few thousand mostly male Bengali workers joined their forebears after restrictions were relaxed.

By 1971, three years after Enoch Powell gave his “Rivers of Blood’’ speech, prime minister Ted Heath decided to pull up the drawbridge. This did not have the desired effect. Bangladeshis, fearful of being cut off and now fleeing a genocidal West Pakistan, rushed to reach their families in Britain. Among them was a young Lutfur Rahman, who, with his mother and older brother, joined his father who had landed a council flat in Bow and a job as a porter at the Savoy hotel.

As Rahman’s family adapted to life in the East End, the Bangladeshi community was forming a protective cluster to shield against the many hostilities facing them. Firstly, a housing shortage—forever a problem in east London. In desperation, families squatted empty council flats, many broken open by an unlikely Irish champion named Terry Fitzpatrick. In 1977, the Bengali Housing Action Group (BHAG) successfully demanded the rehousing of Bangladeshi families in an area now known as Banglatown.

Second was racism. East End Bengalis lived in perpetual fear of the National Front, who patrolled the boundaries of Brick Lane. This came to a head in 1978, when Altab Ali was stabbed to death by skinheads off the Whitechapel Road. After his murder the community attained a Fanonian self-consciousness and a quasi-militant anti-racist movement formed. The Bengalis of Tower Hamlets became an organised force.

The following year, Bengalis began turning up to Labour meetings and demanding entry to the party. One of the first to succeed was Helal Abbas—BHAG’s former secretary, Labour’s first elected Bangladeshi council leader and Rahman’s political mentor. Abbas convinced a young Lutfur—then a promising legal talent—to join Labour, and helped him become a councillor in 2002. Rahman remained under the radar until 2008 when he ousted New Labour’s Denise Jones as council leader.

As mayor, Rahman literally put his face on the side of local infrastructure, including dustbin lorries

Abbas and Rahman learned a lot from each other. But, in 2010, the contest for Labour’s candidate for the newly created office of Tower Hamlets mayor brought an acrimonious split. Rahman beat Abbas in the selection process. Abbas responded by accusing Rahman of having links to Islamists and handed a dossier of now discredited allegations to the National Executive Committee. Rahman was deselected by Labour but ran as an independent. The ensuing campaign got dirty, quickly.

On 15th October 2010, a mysteriously funded special issue of the London Bangla arrived on 90,000 doorsteps baselessly accusing Abbas of racism and beating his wife. There were reports of death threats and competing Brick Lane curry house barons backing each candidate. Both Ken Livingstone (risking his Labour membership) and George Galloway threw their support behind Rahman. When the dust settled, Rahman swept to power on the 22nd October 2010 with over 51 per cent of the vote, becoming the first Muslim executive mayor in the UK, overseeing a budget of £1.1bn.

In his first term, without a majority in the council, Rahman went about impressing himself on Tower Hamlets, in some cases literally putting his face on the side of local infrastructure, including dustbin lorries. Rahman was ambitious. Between 2010 and 2014 his administration built more affordable and social homes than any other local authority in the UK, paid council employees a living wage and largely shielded frontline services from the austerity being unleashed across the country.

However, he seemed allergic to transparency. He failed to show up to 10 overview and scrutiny meetings and maintained a monk-like silence whenever questioned by the opposition. On one occasion the council’s head of legal intervened, suggesting that requiring Rahman to respond was a breach of his human rights. Attention from the media was unrelenting. The Guardian’s Dave Hill devoted acres of column space to Rahman, while Ted Jeory—now a director of the investigative journalism website Finance Uncovered—penned a much-lauded blog criticising the mayor’s tragic hubris and his administration’s lack of accountability.

Some of the coverage was semi-hysterical, particularly that of Andrew Gilligan, a future aide to Boris Johnson who rose to prominence when he cast doubt on the dossier used to justify the invasion of Iraq. By the mid 2010s, Gilligan had become convinced that radical Islamists had infiltrated the council in their quest to bring Sharia law to east London. Some of his reporting on Rahman was deemed “inaccurate and misleading” by the Press Complaints Commission. In 2010, he produced a Dispatches segment on Rahman’s mayoralty for Channel 4 titled “Britain’s Islamic Republic”. (Somewhat ironically, between 2007 and 2009, Gilligan presented a show on Press TV, the state-funded, English-language channel of an actual Islamic republic—Iran.) However, much of the criticism held water. A 2014 Panorama documentary revealed that Rahman’s administration had heavily skewed its spending towards Bangladeshi areas, and that the council had funded an influential local Bengali news station, Channel S, which acted as a kind of personal Pravda for Rahman.

The Panorama coverage prompted the communities and local government secretary, Eric Pickles, to appoint PwC to carry out a Best Value Inspection (BVI) into the council, resulting in the appointment of commissioners to oversee some of its functions. It found that no fraud had occurred but criticised a “culture of cronyism”. On top of this, Rahman scored a number of own goals. Among them was hiring a Mercedes Benz E-Class for £72 each working day and being “tricked” into giving a character reference to a sex offender, then later to an insurance fraudster.

Rahman is eager to establish that he has never been criminally charged for corruption

Despite everything, Rahman was re-elected as mayor in 2014, alongside 18 councillors from his nascent Tower Hamlets First (THF) party. The party was haphazardly assembled. Rahman directed its operation and personally selected its candidates, many of whom offered little beyond blind loyalty. Its financial system was also notably opaque—the party had no bank account and kept track of donations using an Excel spreadsheet.

One year into his new term, disaster struck in the form of an election court judgement. In April 2015, the High Court judge Richard Mawrey ruled Rahman’s re-election void, and that he be disqualified from holding office for five years “on the grounds of corrupt and illegal practices” by him and his agents. However, the Crown Prosecution Service decided that there was insufficient evidence to launch a criminal prosecution.

Mawrey found that three of THF’s councillors had falsely registered to vote and organised others to do the same. “Mr Rahman’s men”, the court found, had also unlawfully completed the voting documents of third parties. Press releases from the mayor’s office were deemed to falsely portray his opponent, John Biggs, as a racist. Rahman, by his agents, was found guilty of bribing local media, instrumentalising grants to promote his campaign and “exerting undue spiritual influence” by using imams to convince Muslims to vote for him. In his afterword, Mawrey wrote that “the alarming state of affairs” could be wholly attributed to “the ruthless ambition of one man.”

Many thought the ruling went too far. Both the London Review of Books and the Guardian claimed that the judge had leaned into unhelpful stereotypes. The Guardian argued that Mawrey had made “unashamed… use [of] a law developed to subdue Irish Catholics.” At a rally supporting Rahman, the chair of the Society of Black Lawyers said that ‘‘racism is alive and well and living in Tower Hamlets… and, yes, sometimes in the judiciary.”

Regardless, Rahman was in ruin. He was fined £250,000 and declared himself bankrupt. He’d lost his livelihood, his office and, most pertinently, his reputation. What followed, however, was not the end of Lutfur Rahman, but one of the most remarkable comebacks in British political history.

Rahman’s office is buried deep within the second floor of the town hall. As we prep in an adjacent room, who should poke his head round the corner with a tea order but Mohammed Jubair, head of the London Bangla Press Club and, perhaps conflictingly, strategic adviser to the mayor. In his first mayoral term, Jubair and Rahman’s dealings were described as “murky in the extreme” by Mawrey. Jubair dispenses tea and recommends a restaurant for later. Apparently he knows the owner.

This was not an easy interview to arrange. The mayor broadly distrusts media attention. Nevertheless, after multiple delays, we were finally granted 30 minutes with him in his office. (We’re using the word “office” charitably here. It’s more like a chapel. On one side is his giant £50,000 meeting table, on the other, beneath a big mullioned window, is what appears to be a throne.)

The few journalists who have managed to sit down with Rahman will probably tell you about his charm. “Thank you for taking an interest in me and our affairs,” he says as we begin, leaning forward slightly in his chair and smiling. This is a man who, at his lowest ebb, assembled a new political vehicle for himself and—in just five years—won a referendum to keep the post of directly elected mayor, won that mayoralty and London’s first non-establishment party council majority in over 60 years.

“I would say my politics has a progressive agenda… I’m a social democrat,” he says when asked about his political beliefs. His policy takes on a strongly redistributive bent. This makes sense; poverty has shaped Rahman. As a child, he had no central heating, washed in public baths and used an outside toilet. These experiences have crystallised into a genuine empathy for the dispossessed.

Rahman doesn’t go into detail about the time proceeding his downfall in 2015. His summary ends ambiguously. “It was a very difficult time… God knows what could’ve happened.” The Mawrey report took a heavy toll on his ageing father, who was humiliated and became bed-bound. During his exile, Rahman used his surplus of free time to care for him. “That was a blessing, indirectly,” he says, forever the optimist. “For every downturn, there’s always a positive.”

With regards to the report itself, Rahman is intransigent. To him, Mawrey’s intervention amounted to a democratic coup. “To my last breath, I will never accept that report,” he says, eager to establish that he was never criminally charged. He adds that “£3.5m was spent on those [263] allegations. Four investigations [and] none of them came to anything at all.”

He may not have been criminally charged, but the report undeniably revealed unsavoury electoral tactics by his camp. Rahman, giving no quarter, expounds a lengthy, legalistic defence, picking apart Mawrey’s charges one by one: false statements are subjective, the bribery charges lacked supportive evidence, absence of criminality is tantamount to vindication, and so on. “I would never lie under oath,” he says, “I fear God, not Justice Mawrey…”

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what drives Rahman or why anyone, having been so robustly assailed, would ever return to public life. “I came into this world naked,” he says, “and I will leave it in a shroud… I’ve got nothing to lose.”

Rahman re-entered politics in 2017. After his first attempt to register a new party was rejected, he successfully launched Aspire with councillors left over from Tower Hamlets First. The party failed to win any seats in the 2018 election. However, when Rahman returned from exile in 2022, it won 24, usurping Labour’s supermajority.

Aspire’s 2022 intake, apparently selected by the party membership, was sexually and ethnically homogenous. On the party’s lack of women, Rahman’s initial response is weak, telling us that some of his biggest supporters are women, which isn’t what we asked. Aspire did field three female candidates, but all of them in Labour safe seats, which Rahman defends: “They chose those wards.”

Rahman is a populist, not an easy approach in the context of local government, where horizons generally don’t extend beyond the maintenance of basic services. However, Rahman likes to push the boundaries, exercising virtually every power legally permissible. Mawrey described him as autocratic and the most powerful executive mayor in Britain. Rahman laughs at this diagnosis: “I hope so.”

In the last two years, Aspire has put forward successful policies and bold pledges, but there’s a gap between the party’s rhetoric and the reality. The party recently reneged on a promise to freeze council tax, albeit exempting households with incomes under £50,000. It is dramatically failing to meet its unrealistic housing targets and has alienated green-minded voters with its decision to scrap low-traffic neighbourhoods, for which the council was stripped of £1m in funding by Transport for London. Rahman’s Keynesian approach to public service provision has faced heavy criticism from opposition benches. One Local Government Association report also raised concerns that poor relations between senior officers and the well-staffed mayor’s office were delaying decision-making.

Then, on 22nd February, the mayor’s office was notified of another BVI, sanctioned by Michael Gove’s office, to ascertain whether Tower Hamlets council is delivering a “continually improving”, economic and effective service. This time, government concern related to the centralisation of power in the mayor’s office, accountability (Rahman’s poor attendance at overview and scrutiny meetings has continued since re-election), grant-making, financial planning and lack of senior management at the council.

Rahman likely sees the inspection as the first step in another politically motivated campaign to remove him from office. The findings, which will be released in May, could absolve the mayor, or validate his most vocal detractors. In a press briefing, Rahman’s office called the BVI announcement a “clear attempt to undermine the votes of the residents of the borough for the second time.”

Inspections aside, Aspire has managed to balance its budget while delivering a meaningful poverty reduction policy in a borough with the highest child deprivation rate in the UK. Moreover, a gaping vacuum has opened up on the left of British politics. Starmer has taken the support of young people and Muslims for granted in his many discarded pledges and his Gaza stance. Rahman recognises this. “It’s really sad,” he says, “I would’ve thought politicians would have a lot more humanity… if we’re calling out the Russians in Ukraine, we’ve got to call out the Israelis in Palestine.”

Finally, we reach the fundamental question—will Aspire run parliamentary candidates in the upcoming election? They could do this solely in Tower Hamlets’ two seats, or, more likely, as part of a wider nationwide coalition backed by TMV and established left-wing groups. He’s been asked this a lot recently. First the mayor tries to deflect, saying it’s a question for Aspire’s executive committee. However, we all know who calls the shots around here. Pressed again, Rahman concedes. “The party is considering it,” he says, “they will take a view in due course. There are a lot of discussions [on this] within the party and I’m not discouraging it… but the party hasn’t taken a formal view.”

At this point, the mayor’s head of comms interrupts to call time. However, before we conclude, we’re privy to one final statement. “I’m not a powerful figure, I’m just an ordinary bloke who’s been given a chance by the people of this borough to serve them. That’s all.” We’re left in a slight daze, looking up at his enormous office. On our way out we pass Rahman, trying on a wide-brimmed Stetson hat for some reason. He quickly removes it and waves us goodbye. An hour later, we arrive at a local curry house to find two biryanis, mango lassis and a mixed grill waiting for us, free of charge.